Click here to download our informational pamphlet: "Skin Cancer: An Introduction for Organ Transplant Recipients"

Haga clic aquí para descargar la pampleta: "Cancer de Piel: Una Introduccion para Recipientes de Transplante de Organo"

This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace the advice of your doctor or health care provider. We encourage you to discuss with your doctor any questions or concerns you may have.

Click on the following topics to learn more:

- Risk Factors for Skin Cancer

- Types of Skin Cancer

- Medical Treatment

- Surgical Treatment

- Follow-Up Care

- Self Skin Exam

- Preventing Skin Cancer

- Additional Resources

- Skin Cancer Research: What's New?

Risk Factors For Skin Cancer

Risk factors are a clue to each individuals risk for developing skin cancer. In general, the more risk factors, the more likely a skin cancer may develop.

General risk factors:

- History of significant sun exposure

- Fair skin, skin that burns easily, rarely tans

- History of multiple blistering sunburns

- History of radiation exposure

- Also see risk factors for the general population

Organ Transplant Recipients are at high risk for developing skin cancer

As people with transplants survive longer, the long term effects and complications are becoming more apparent. One complication is skin cancer.

Transplant patients have up at 100-fold higher risk for developing skin cancer compared to the general population. Transplant patients tend to develop a skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) although many patients will also develop a different type of skin cancer called basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

The frequency at which SCC occurs in transplant patients is 65-fold higher than the general population.

Transplant patients also develop other skin cancers. This table shows the increase in incidence for various types of skin cancer:

| Skin Cancer | Increase in Incidence |

|---|---|

| SCC | 65-fold |

| SCC of lip | 20-fold |

| BCC | 10-fold |

| Melanoma | 3.4-fold |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | 84-fold |

Your risk for skin cancer increases each year following transplantation.

All transplant patients have a greater chance of developing skin cancer compared to the general population. This risk increases with each subsequent year following your transplant.

At 5 years after transplant, some studies suggest that approximately 5% of transplant patients will develop skin cancer. At 10-years, approximately 10% of transplant patients develop skin cancer(1). The risk for skin cancer may vary with the type of transplant. Cardiac and kidney transplant patients seem to develop skin cancer more frequently than liver or lung transplant patients(2). However, all transplant patients are at higher risk for skin cancer compared to the general population.

Skin cancer in transplant patients can be life threatening and affect quality of life:

Untreated skin cancer invades and destroys tissue. It can lead to disfigurement and loss of function. In rare cases, skin cancer can metastasize. The metastasis rate in transplant patients is 3-4 fold higher than that of the general population and can be life threatening.

The keys to successfully treating skin cancer while minimizing any side effects are early detection and treatment.

The main skin cancer that occurs in transplant patients is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). SCC that occurs in transplant patients can behave differently than SCCs that occur in the general population even thought they may look the same. SCC that occur in transplant patients tend to:

- Develop at younger age

- Develop more quickly

- Occur in greater numbers

- Be more invasive and locally destructive

- Have a greater risk for recurrence (regrowth of tumor at a previously treated area)

- Have a greater risk for metastasis (tumor breaks off and travels to lymph nodes or other distant sites of the body)

Risk factors specific for Transplant patients:

- Prior history of actinic keratosis (pre-cancers)

- Prior history of skin cancer

- Older age at transplant

- Duration and intensity of immunosuppression

- Type of organ; heart recipients > kidney recipients > liver recipients

Overexposure to sunlight is a major risk factor. The more sunlight your skin has been exposed to during your lifetime, the higher your risk for developing skin cancer. Because UV radiation in linked to skin cancer, transplant patients tend to get skin cancer on be sun exposed areas (face, ears, scalp, neck, backs of hands and backs of forearms).

Some sites where skin cancer occurs that may be associated with an increased chance or recurrence or metastasis includes the ear, lip, perioral region, periorbital region, nose and genitalia.

The majority of sun damage occurs before the age of 30, however, good sun protection at any age may be beneficial at preventing future skin cancers.

Immunosuppressive mediations are essential to prevent graft rejection and to optimize graft survival. However, because these medications suppress the immune system, whose main function is to fight off infection and prevent the development of cancer, transplant recipients are at elevated risk for infection and certain cancers.

The exact mechanism by which immunosuppressive medications promote tumor growth is currently being studied. However, several lines of evidence suggest the duration, intensity and type of immunosuppressant may be related to the development of skin cancer.

Transplant patients have an increased incidence of:

- Skin cancer (most common)

- Lymphoma

- Cervial cancer

- Liver cancer

Types of Skin Cancers

- Actinic Keratosis

- Basal Cell Carcinoma

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Melanoma

- Kaposi's Sarcoma

- Anogenital Carcinoma

Actinic Keratosis

- Rough, red or pink scaly patches on sun-exposed areas of the skin,usually <0.5cm in diameter

- Precurser lesion for squamous cell carcinoma

- Up to 1% of these lesions can develop into a Squamous Cell Carcinoma

An early warning sign of skin cancer is the development of an actinic keratosis. Actinic keratoses are precancerous skin lesions that result from chronic sun exposure. They are typically < 0.5cm in diameter, pink or red in color and rough or scaly to the touch. They occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin (face, scalp, ears, backs of hands or forearms). Actinic keratoses may start as small, red, flat spots but grow larger and become scaly or thick, if untreated. Sometimes they are easier to feel than to see. There may be multiple lesions next to each other.

Early treatment of actinic keratoses may prevent their change to cancer. These precancerous lesions affect more than 10 million Americans. People with one actinic keratosis usually develop more. Up to 1% of these lesions can develop into a squamous cell cancer.

Actinic keratoses are most common in people older than 40, but can also appear in younger individuals with extensive sun exposure. Because they can turn cancerous affected areas should be regularly examined and treated by a primary care physician or dermatologist.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

- Raised, pink, waxy bumps that may bleed following minor injury

- May have superficial blood vessels and a central depression

- Locally invasive

- Rarely metastasizes

- Organ transplant recipients have a 10-fold higher risk for Basal Cell Carcinoma compared to the general population (5)

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of non-melanoma skin cancer. This type of cancer often looks like a pink waxy bump that may bleed following minor injury. There may be irregular blood vessels on its surface and its center may be sunken in. Large basal cell carcinomas may have oozing or crusted areas.

Basal cell carcinomas typically occur on sun-exposed skin of the face, ears, neck and trunk but may also occur on the arms or legs. Basal cell carcinomas grow slowly and rarely spread to other parts of the body (metastasize). However, if left untreated, they can become locally invasive and destroy surrounding muscle, bone and nerves causing significant disfigurement and functional problems.

There are several subtypes of basal cell carcinoma. Some are more aggressive than others. The subtype of basal cell carcinoma is identified by skin biopsy and examination under a microscope.

What causes basal cell carcinoma? The most common cause of basal cell carcinoma is ultraviolet light (UV), specifically ultraviolet B (UVB, 290-320 nm). Indoor tanning, fair-skinned complexion, prior radiation exposure and inherited genetic conditions such as nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome or Basex's syndrome are other important risks factors.

Translucent pearly pink papule near the right eye.

This tumor has the characteristic translucent, pearly quality with superficial blood vessels. Notice its depressed, almost scar-like appearance, commonly seen in the infiltrative subtype of basal cell carcinomas.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Dull red, rough, scaly raised skin lesions

- Occur most frequently on sun exposed areas (head, neck, ears, lips, back of the hands and forearms)

- Sites particularly associated with elevated risk for recurrence or metastasis include: ear, lip/perioral, nose, periorbital, genitalia

- Most common skin cancer that occurs in pediatric and adult transplant recipients

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma tumors can grow very rapidly

- Mutiple cancers can occur simultaneously

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma tends to be more invasive and more aggressive in transplant patients

- Organ transplant recipients have a 65-fold higher risk for Squamous Cell Carcinoma and 20-fold higher risk for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the lip compared to the general population (6)

- Adult transplant patients tend to develop Squamous Cell Carcinoma 5-7 years following transplant

- Pediatric transplant patients (patients who received their transplants before the age of 18) tend to develop Squamous Cell Carcinoma an average of 10 years following transplant (7)

- Pediatric transplant patient have higher risk for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the lip compared to adult transplant patients

- Local recurrance rate ~13% in adult transplant patients (8, 9)

- Metastatic rate ~2% in general population

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinomas are often described as enlarging red bumps, sometimes with a rough, scaly, or crusted surface. They may also look like flat reddish patches in the skin that grow slowly. If untreated, they can become ulcerated (open sores). Most squamous cell carcinomas grow slowly. Occasionally, they may occur quite rapidly, particularly in patients who are immunosuppressed.

Squamous cell carcinomas occur most frequently on sun-exposed areas such as the head, neck, ears, lips, back of the hands and forearms.

This cancer rarely metastasizes (spreads to lymph nodes or other organs), although distant spread happens more frequently than in basal cell carcinoma. The squamous cell carcinoma that has metastasized typically is:

- greater than 2cm in diameter or greater than 4mm in depth

- in a site previously exposed to radiation

- in a patient with a history of solid-organ transplantation

When squamous cell carcinoma does metastasize, it most commonly travels to the local lymph nodes.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in organ transplant recipients.

Melanoma

- Neoplasm of pigment (melanin) producing cells

- Brown or black skin lesion with irregularities in symmetry, border and coloration

- Prognosis dependent on depth of invasion

~100,000 new cases of melanoma are diagnosed in the United States each year- Only 4% of diagnosed skin cancer, but 77% of skin cancer related deaths

- Organ transplant recipients have a 3 to 4-fold higher risk for melanoma compared to general population (1)

- Melanoma accounts for ~6% of post transplant skin cancers in adult transplant recipients (7)

- Melanoma accounts for 12-15% of post transplant skin cancers in pediatric organ transplant recipients (7)

- Transplant recipients with a pre-transplant history of melanoma have a high risk of recurrence (~20%) (11)

Melanoma is the most dangerous type of skin cancer. Although melanoma makes up only 4% of skin cancers, it causes 77% of skin cancer deaths. About 100,000 cases of melanoma are diagnosed each year.

Melanoma typically presents as a brown or black spot with irregularities in symmetry, border and color. Melanoma may develop within an existing mole or on previously normal appearing skin. Melanoma has a high fatality rate because its cells can break off and spread throughout the body (metastasize).

When melanoma is caught early, your chances for successful treatment are much higher.

The ABCDEs of Melanoma

These characteristics are used by dermatologists to classify melanomas. Look for these signs: Asymmetry, irregular Borders, more than one or uneven distribution of Color, or a large (greater than 6mm) Diameter. Finally, pay attention to the Evolution of your moles - know what's normal for your skin and check it regularly for changes.

If you see one or more of these, make an appointment with a dermatologist immediately. Please note that not all melanomas fall within the ABCDE parameters so visit your dermatologist regularly to catch any potiential issues early.

|

A - Asymmetrical ShapeMelanoma lesions are often irregular, or not symmetrical, in shape. Benign moles are usually symmetrical. |

|

B - BorderTypically, non-cancerous moles have smooth, even borders. Melanoma lesions usually have irregular borders that are difficult to define. |

|

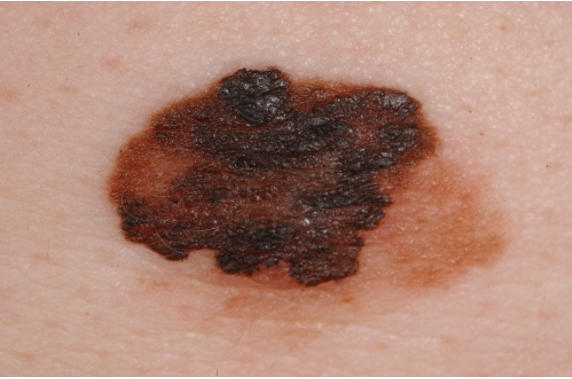

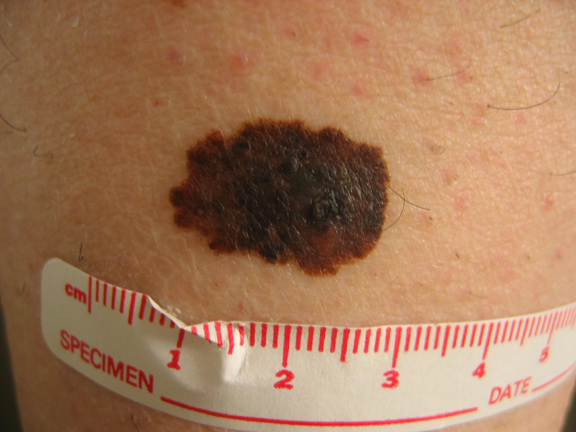

C - ColorThe presence of more than one color (blue, black, brown, tan, etc.) or the uneven distribution of color can sometimes be a warning sign of melanoma. Benign moles are usually a single shade of brown or tan. |

|

D - DiameterMelanoma lesions are often greater than 6 millimeters in diameter (approximately the size of a pencil eraser). |

E - Evolution

The evolution of your mole(s) has become the most important factor to consider when it comes to diagnosing a melanoma. Knowing what is normal for YOU could save your life. If a mole has gone through recent changes in color and/or size, bring it to the attention of a dermatologist immediately.

This 38 year old patient noticed that a previously flat mole had changed and become larger in diameter and protruded outward from his skin (This fulfills the E for Evolution rule of the ABCDE’s).

Melanoma can occur in unusual areas, including the hands, feet and even the eye

This melanoma is asymmetric, has an irregular border, has multiple colors within the lesion (brown, black, tan) and is > 0.6cm in diameter.

Kaposi's Sarcoma

- Rare, cancer of the cells that line blood vessels (endothelial cells)

- Clinically: brownish-red to blue colored skin lesions found most frequently on legs and feet

- Caused by Human Herpes Virus 8 (HHV-8) which causes the cells that line blood vessels (endothelial cells) to become cancerous in the setting of profound and prolonged immunosuppression

- Typically occurs in patients of Middle Eastern, Jewish, Mediterranean or African descent where HHV-8 in endemic

- Two main forms of Kaposi's Sarcoma exist

- Cutaneous/Mucocutaneous

- Visceral

- Most common form that occurs in pediatric transplant patients (7)

- Most pediatric cases occur while the patient is < 18 years old

- Kaposi's Sarcoma tumors can affect the gastrointestinal system, lymph nodes and lungs

- The visceral form is considered more serious than the cutaneous/mucocutaneous form

Anogenital Carcinoma

- These include tumors of the vulva, scrotum, penis, perianal skin and anus

- Occur at 30-100 fold higher incidence in transplant patients than the general population

- Most common in females

- Ratio of female to male patients 2 to 1 (adult transplant patients)

- Ratio of female to male patients 8.5 to 1 (pediatric transplant patients)

- Tend to occur ~12 yrs after transplantation (mean age of 27y/o) in pediatric transplant patients and ~7yrs after transplant in adult transplant recipients

- Clinically:

- Tend to be multiple, extensive, or both

- May resemble wart-like lesions

- Risk factors include:

- Mutiple sexual partners, HPV infection, hx of herpes genitalis, heavy smoking, high level of immunosuppression

- Post-adolescent female transplant recipients should have regular gynecologic examination of the anogenital region

Medical Treatment for Skin Cancers

Topical Field therapy

- COX-2 inhibitors (AKs)

- Topical Retinoids (AKs, superficial BCC)

- 5-FU (AK, superficial BCC, SCCIS)

- Effudex® or Carac®

- Topical chemotherapy for the skin

- Excellent choice for numerous actinic keratoses

- Preferentially absorbed by the precancerous or cancerous cells

- Apply 2x/day for 3-4 weeks

- Skin turns red and crusty- like a very bad sunburn

- Visible and sub-clinical lesions “light up”

- Imiquimod (AKs, superficial BCC, SCCIS)

- Immune response modulator

- Stimulates the immune system in the skin to recognize and destroy precancerous and cancerous cells

- Cream is applied several times a week

- Skin turns red and crusty during the course of treatment- if no reaction occurs, need to increase the frequency of application

Acitretin

- Reduces the rate at which new skin cancers appear

- Benefit only when taking medication

- Potential candidates: patients with >5 skin cancers/year

- Side effects: liver toxicity, elevated cholesterol, dry skin

Reduction of immunosuppression

- Consider when benefits outweigh risks

- Potential candidates:

- Metastatic skin cancer of any type

- >5 to 10 skin cancers/year

- Kaposi's Sarcoma

- Post Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder

Other options

- Bleomycin

- Radiation

- Chemotherapy

- Consider adjusting immunosuppressive regimen by switching to less carcinogenic medications

Surgical Treatment for Skin Cancer

- Cryosurgery

- Very cold! (-321°F or -196°C)

- Treatment of choice for individual pre-cancers

- Applied with a spray gun or cotton tipped applicator

- A burning or “frostbite sting” sensation is felt

- Treated areas turn red, swollen, and sometimes blister during healing

- Currettage with electrodessication

- Precancerous lesions are scraped away with a curette

- Then the area is cauterized with an electric needle to control bleeding and kill any remaining cancerous cells

- Photodynamic therapy

- A light-sensitizing solution is applied to the skin and allowed to absorb over several hours

- Chemical is selectively absorbed by the abnormal cells

- An activating light is shined on the patient, causing destruction of the abnormal cells

- Burning sensation is experienced

- Lesions turn red and crusty

- Patients must avoid any sun exposure after treatment, as their skin is still light sensitive

- Ablative skin resurfacing (resurfacing laser, dermabrasion, chemical peel)

- Laser or chemicals are used to remove the outer layers of the skin

- As the treated skin peels, new skin forms to replace it

- Redness and swelling are seen for several days/weeks after the treatment

- Can have pigment changes and scarring

- Excision and split-thickness skin grafting of the dorsa of the hand and forearm

- Mohs micrographic surgery

- Technique of surgery that has the highest five-year cure rates for surgical treatment of both primary (96 %) and recurrent (90 %) skin cancers

- Removes all of the cancerous tissue and as little of the healthy tissue as possible to minimize scaring and maximize cosmetic outcome

- The cancer is shaved off one thin layer at a time. Each layer is checked under a microscope until the entire tumor is removed

- This method should be used only by physicians who are specially trained in this type of surgery

Read more about Mohs micrographic surgery

- Excision with intraoperative frozen section control

- Excision with postoperative margin assessment

- Excision with Sentinal Lymph Node Biopsy

Follow-up Care

Not all transplant recipients will develop skin cancer, however all transplant patients are encouraged to examine their skin for worrisome lesions once a month (see self skin-exams), follow-up with their dermatologist for regular skin checks, and practice adequate sun protection measures (see skin cancer prevention).

Transplant Patients should see a Dermatologist at least every 1-2 years for life

Since all organ transplant patients are at elevated risk for skin cancer, the most recent guidelines advise all transplant patients to have head-to-toe skin exams performed by a dermatologist at least every 1-2 years for the remainder of their lifetime. Sometimes, patients will be asked to visit their dermatologist more frequently, especially if they have multiple risk factors for developing skin cancer.

Some examples of risk factors that would indicate the need for more frequent skin exams are a prior history of skin cancer or a history of pre-cancerous skin lesions like actinic keratosis. Patients should visit their dermatologist within 1-year following their transplant to establish care. At minimum, transplant patients should see a dermatologist at least once every 1-2 years.

If you are a pre-transplant candidate and have a history of skin cancer, you should notify your transplant physician. Sometimes, you will be asked to have a skin examination with a dermatologist prior to your transplant. Alternatively, you should see a dermatologist within 6 months following your transplant to establish care. Any patient who has had skin cancer is at high risk for developing additional skin cancers in the future.

A rough guideline to the frequency with which transplant patients should be examined by a Dermatologist is given in the following table:

| Patient Characteristic | Frequency of Dermatology Exam |

|---|---|

| No history of skin cancer or Actinic Keratosis | Every 1-2 years |

| History of Actinic Keratosis | Every 6 months |

| History of 1 non-melanoma skin cancer | Every 6 months |

| History of multiple non-melanoma skin cancer | Every 3 to 4 months |

| History of high risk SCC or melanoma | Every 2 to 3 months |

| History of metastatic SCC | Every 1 to 2 months |

Self Skin Exam

How to Examine Your Skin

It's important to check your own skin, preferably once a month. Self-examination is best done in a well-lit room in front of a full-length mirror. A hand-held mirror can be used for areas that are hard to see. A spouse or close friend or family member may be able to help you with these exams, especially for those hard-to-see areas like the lower back or the back of your thighs.

The first time you inspect your skin, spend a fair amount of time carefully going over the entire surface of your skin. Learn the pattern of moles, blemishes, freckles, and other marks on your skin so that you will notice any changes. Any trouble spots should be seen by a doctor. Follow these step-by-step instructions to perform your skin self-exam:

Face the mirror and have a hand mirror for your thighs, back, and scalp:

Preventing Skin Cancer

Sun Avoidance

Avoiding sunshine can help prevent most types of skin cancer.

- Avoid sun exposure as much as possible between the hours of 10AM and 4PM

- Don't stay in the sun for prolonged periods of time, even if you are wearing sunscreen

- Seek shade

- Avoid tanning beds

- Even on cloudy days, 80% of sun’s UV rays reach you

You do not have to avoid the sun altogether. Learn how to protect your skin from the sun's harmful rays and practice "sun protection" and "sun safety" whenever you can. Cover up with sunscreen and protective clothing and be sensible about how much time you spend in the sun. These steps can help greatly reduce your risk of developing skin cancer.

Sunblock

Sunblock protects your skin by absorbing and/or reflecting UVA and UVB radiation. All sunblocks have a Sun Protection Factor (SPF) rating. The SPF rating indicates how long a sunscreen remains effective on the skin. A user can determine how long their sunblock will be effective by multiplying the SPF factor by the length of time it takes for him or her to suffer a burn without sunscreen.

For instance, if you normally develop a sunburn in 10 minutes without wearing a sunscreen, a sunscreen with an SPF of 15 will protect you for 150 minutes (10 minutes multiplied by the SPF of 15). Although sunscreen use helps minimize sun damage, no sunscreen completely blocks all wavelengths of UV light. Wearing sun protective clothing and avoiding sun exposure from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. will also help protect your skin from overexposure and minimize sun damage.

The American Association of Dermatology (AAD) recommends that a "broad spectrum" sunblock with an SPF of at least 15 that is applied daily to all sun exposed areas, then reapplied every two hours. However, in some recent clinical trials, sunblocks with SPF 30 provided significantly better protection than sunblocks with SPF15. Therefore at UCSF, we recommend sunblocks with SPF of at least 30 with frequent reapplication.

Use broad spectrum sunscreen daily with SPF of 30 or greater- UVA/UVB protection.

- Apply ~30 minutes prior to sun-exposure.

- Apply to all sun-exposed areas. Don't forget lips, ears, back of neck, or back of legs.

- Apply a sufficient coat of sunscreen- most common mistake is being too stingy

- Reapply every 2 hours when out in the sun- more frequently if in water or sweating

- Use lip balm with sun block daily that is frequently reapplied

- Chemical sunblocks- these function by absorbing the harmful energy of sunlight before it reaches your skin

- Most chemicals used in sunblock only provide protection over a narrow range of UV radiation. Therefore, sunblocks often use combinations of chemical blockers to provide broad spectrum protection.

- USCF typically recommends chemical sunblocks that contain Parsol 1789 (avobenzone) because of its superior protection against UVA radiation

- Mexoryl (Anthelios) is another chemical sunblock that provides excellent broad spectrum UVA and UVB protection. It is not approved for use in the United States by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) but is sold in Europe and Canada, often through internet sites.

- Physical blockers- contain ingredients that scatter UV radiation before it reaches your skin

- Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are the only two physical sunblocks are generally considered equally effective

both offer broad spectrum UVA and UVB protection

good for sensitive skin

- Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are the only two physical sunblocks are generally considered equally effective

Sun Protective Clothing

Clothing is a simple and effective sun protection tool. It provides a physical block that doesn't wash or wear off and can shade the skin from both UVA and UVB rays. Long-sleeved shirts and pants, hats with broad brims and sunglasses are all effective forms of sun protective clothing.

The American Society for Testing and Materials has recently developed standards for manufacture and labeling of sun protective products. The new units for UV protection are called UPF (Ultraviolet Protection Factor). UPF measures the ability of the fabric to block UV from passing through it and reaching the skin.

- Good UV Protection (for UPF 15-24),

- Very Good UV protection (for UPF 25-39), or

- Excellent UV Protection (for UPF 40-50)

Not all fabrics block UV light to the same extent. The Ultraviolet protective factor (UPF) of clothing depends on several factors including weave and chemical additives when manufactured, (such as UV absorbers or UV diffusers).

UPF factors in order of importance:

- Weave: tightly woven fabric provides greater protection than loosely woven clothing. If you can see light through a fabric, UV rays can get through, too.

- Color: Dark colors provide more protection than light colors by preventing more UV rays from reaching your skin.

- Weight: also called mass or cover factor - heavier is better

- Stretch: Clothing with less stretch generally has better UV protection

- Wetness: Dry fabric is generally more protective than wet fabric.

The ideal sun-protective fabrics are lightweight, comfortable, and protect against exposure even when wet. Currently, only a few companies in the U.S. manufacture clothing that is specifically designed to be UV-protective. Their products include outerwear, pants, shirts, and hats for all sizes and shapes including children. See the sidebar at the left for recommended websites.

For those who enjoy water sports, consider using UV protective swimwear including rash guards and swimsuits. Some companies even sell UV protective flotation devices and swim diapers.

Additionally, you may use sunprotective clothing additives such as Sunguard Detergent. Sunguard detergent is an UV blocking additive that can be added to your laundry to transform everyday clothing into sun protective gear with a SPF 30. The active ingredient is Tinosorb™ FD, a UV protectant that can boost the SPF protection of a white cotton T-shirt from SPF 5 to UPF 30.

References

- L. Naldi et al., Transplantation 70, 1479 (Nov 27, 2000).

- R. Adamson et al., Transplant Proc 30, 1124 (Jun, 1998).

- C. Traywick, F. M. Reilly, Dermatologic Therapy 18, 12 (2005).

- P. Jensen et al., J Am Acad Dermatol 40, 177 (Feb, 1999).

- P. Jensen et al., Transplant Proc 31, 1120 (Feb-Mar, 1999).

- I. Penn, Pediatr Transplant 2, 56 (Feb, 1998).

- J. A. Carucci et al., Dermatologic Surgery 30, 651 (2004).

- J. A. Carucci, Semin Cutan Med Surg 22, 177 (Sep, 2003).

- J.-C. Martinez et al., Arch Dermatol 139, 301 (March 1, 2003, 2003).

- I. Penn, Transplantation 61, 274 (Jan 27, 1996).

- S. Euvrard, J. Kanitakis, A. Claudy, N Engl J Med 348, 1681 (Apr 24, 2003).

- A. Gutierrez-Dalmau, J. M. Campistol, N Engl J Med 353, 846 (Aug 25, 2005)

Skin Cancer Research: What's New?

There is much to learn about skin cancer —especially its connection with transplant patients. Therefore, it is important to stay up-to-date with new research. Below are summaries of articles recently published in various scientific journals that discuss skin cancer topics for transplant patients.

Association of HLA Antigen Mismatch With Risk of Developing Skin Cancer After Solid-Organ Transplant

Published in JAMA Dermatology (January 2019)

Summary: Skin cancer after organ transplantation is driven by a combination of sun exposure and systemic immunosuppression. Physicians already knew that older, white male patients with a lifetime of high sun exposure are at greater risk for skin cancer, but studying the immune system and skin cancer risk has been more difficult.

Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) are proteins in our bodies that our immune system uses to distinguish foreign cells from our own cells. When patients are transplanted, we look at the HLA match between donor and recipient since a closer match can lead to better outcomes.

In this study, we looked at the match between organ donor and transplant recipient, and discovered that heart and lung transplant recipients with HLA mismatches actually had less skin cancer than those with a closer match. This suggests that the immune system of patients with mismatches may still be able to recognize and fight off skin cancer cells despite the high level of immunosuppression required to protect the transplanted organ. Future studies are still needed to learn how different immunosuppressive drugs impact this finding.